February

16, 2021

Recollections of Education Policy Analysis Archives &

Things Related To

It.

I came to Arizona State University in August, 1986, to retire and play tennis. Who knew?

I never intended to spend the three summer months in Phoenix. I would return to Boulder, Colorado, to escape the heat. But I did so with feelings of guilt for having abandoned colleagues and students. I had been accustomed for twenty some years to being accessible in person to any and all. It seemed like a godsend, then, in 1988 when a grad student in education technology came to my office and showed me this new phenomenon called “electronic mail.” My prayers had been answered. Here was a way to communicate with students and colleagues as much as I desired without the cost of long distance phone call charges or the delay of postal mail.

I immediately began to use email, and then file transfer, and then synchronous chat with the PhD students in the Proseminar, which I taught for several years after the inception of the program. Soon, students were submitting their written work via email – not just to me but to their fellow students as well.

It was now 1989 and in March, Tim Berners-Lee at CERN was writing a document

called “Information Management: A Proposal.” Soon after, a computer science

undergraduate at the University of Illinois –

Marc Andreessen – was coding what was to become the Mosaic web browser. Text

and images were seamlessly integrated into documents. When printed, web pages

looked exactly like what any book publisher could produce.

The

potential of what was showing up on my desk computer was not lost on me. My

long latent interest in computers was instantly rekindled. I hadn’t touched a

computer since 1962. As an undergraduate at the University of Nebraska in 1959,

I had had the good fortune to meet by chance a new Princeton PhD by the name of

Robert Stake. Stake had a contract with the military to explore an obscure area

of multi-dimensional scaling. The work was Monte Carlo analysis, and the state

of the art computer of the time as a Burroughs 205 – a clunker of a

machine that was destined to be spray painted black by a Hollywood stage hand

and serve as the Batcomputer on the Batman TV series. I told Stake that I was a

computer programmer – I wasn’t; I was a janitor – and that I could

build his programs for him. He bought the story, and my life changed.

By

1962 when I started grad school at Wisconsin, I had been forced to learn three

different computer languages just to keep up. I saw no future in that

occupation, and I gave up on computers just before university mainframes were

beginning to install FORTRAN compilers. But in 1993, this world

wide web thing was something different. I learned the web language html

and started to build webpages. Then, when the secretaries’ desktop computers

could no longer handle the latest version of WordPerfect, they gave them to me,

and I turned them into web servers. At one point my office held eight PCs,

seven of them serving web content. I convinced Bill Russell and the AERA Board

that AERA needed to be on the net. I registered the domain name aera.net in

1996 – the Automobile Engine Repair Association beat us to aera.com

– and operated the AERA web from my office for five or so years until it

was taken over by the Central Office. I learned a primitive graphics program to

produce the image for the homepage:

EDPOLYAN,

EPAA’s Forebearer

Prosem

students were taught more about the Internet than they wanted to know. I blush

as I look back now at how I assumed their interests were the same as mine and how I shortchanged them. In 1990, I found a way

to join the attraction I felt for this new world of the Internet with my

profession, such as it was, education policy. An Internet discussion program was

spreading across the academic world. LISTSERV was the creation of Eric Thomas,

a young student in Paris who soon relocated to Stockholm. An email sent to a

particular address, e.g., listname@LISTSERV.asu.edu

could be immediately distributed to a long list of “subscribers,” then

archived, made available for word search, and otherwise made available to users

everywhere. I decided to create a LISTSERV and named it EDPOLYAN, for education

policy analysis. Now my colleagues and students could know that I was also

interested in what I was being paid to do.

EDPOLYAN was created January 4, 1990. It was reviewed in 1992 by Raleigh C. Muns (Reference Librarian) Thomas Jefferson Library, University of Missouri, St. Louis:

EDPOLYAN seamlessly mixes the contributions of K-12 instructors and administrators with university level policy wonks. Postings are terse, dry, and to the point (definitely a compliment). … Apparently unmoderated, the group's message stream nonetheless exhibits characteristics of moderated lists in its terseness and ability to maintain discussions relevant to the topic of education. Don't expect entertainment here; do expect utility. EDPOLYAN is one of those rare discussion groups that is exactly what it purports to be.

At the time of Muns’s review, EDPOLYAN had 467 subscribers in 13 countries. Over the next three years, EDPOLYAN grew to nearly 1,000 participants, or “subscribers.” The five-year existence of EDPOLYAN bore many fruits. Persons who otherwise lacked a public forum to express their opinions and demonstrate their scholarship found one in EDPOLYAN. Several scholars began to be recognized for their valuable thinking about education policy: AG Rud, then at Purdue; Sherman Dorn, still a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania when EDPOLYAN was created in 1990; Benjamin Levin before his contretemps; Aimee Howley; Thomas Mauhs-Pugh; Les McLean; and many others.

Not all EDPOLYAN contributors lacked a public voice. Tom Green, philosopher of education at Syracuse – and a fellow Nebraskan, I hasten to add – was a frequent and highly valued participant. And one important contributor had no visibility outside of the Internet whatsoever. Rick Garlikov was, and still is, a professional photographer living in Birmingham, Alabama. Rick had been a PhD student at the University of Michigan, studying under the famous Abraham Kaplan. As the first step toward the dissertation hurdle, Rick submitted a 100-page proposal to Kaplan; it’s title? The Nature of Love. Eighteen months passed, but Kaplan did not reply or mention the prospectus. Rick took the hint and left the university. Rick’s thinking on subjects like education policy was fresh and insightful and unscarred by the fads that periodically grip the thinking of certified members of the Academy. He maintains a website where much of his thinking on topics such as ethics, and yes, love, are archived: http://garlikov.com.

Another invisible contributor passed through EDPOLYAN on his way to national visibility. Andrew Coulson was a young computer programmer from Montreal who had played a key role in the construction of Microsoft WORD. In his late 20s, he was living in Seattle in virtual retirement. He had an interest in schooling, and he happened upon EDPOLYAN. His contributions were first-rate: intelligent, well crafted, and evidencing an understanding of organizations and society remarkable in one so young. Coulson saw things through conservative, market-based eyes. I later invited him to serve on the initial Editorial Board of EPAA. He published two major papers in EPAA: Vol 4 (1996) Markets Versus Monopolies in Education, and Vol 2 (1994) Human Life, Human Organizations and Education. Andrew later became a key player in the analysis of education policy at Stanford’s Hoover Institution and at the CATO Institute. Sadly, he died of glioblastoma on February 7, 2016, at age 48. I believe his life’s work was changed by EDPOLYAN and EPAA.

EDPOLYAN had some of the best discussions of education policy I have ever been a part of or read in any journal or book. Synchronous debate among a large group has the potential of reaching the highest levels of scholarship in certain fields. In 1994, a discussion began on EDPOLYAN of what was the Tennessee Value Added Assessment System. The TVAAS was to be come the foundation of the Obama administration’s Race To The Top program 15 years later. More than a dozen persons contributed to the EDPOLYAN discussion of TVAAS. Some original data analyses were presented. The TVAAS creator – William Sanders – appeared briefly, then he disappeared. The final form of the discussion, lightly edited, numbers more than 60,000 words, a small book. If the messages coming from that discussion had been heeded widely, the world would be a better place today. I have formatted that discussion for the web and placed it here: http://ed2worlds.blogspot.com/2020/04/an-archaeological-dig-for-vam.html

However, not everything was beer and skittles at EDPOLYAN. As it matured, EDPOLYAN began to evidence the stresses and strains so familiar now to online public debate. Some postings got personal; some hurled insults; and finally, certain exchanges got downright nasty. Perhaps any group of 1,000 individuals will contain a few malcontents and jerks. EDPOLYAN had a few, but very few. In early 1995, they were beginning to concern me. My attempt to counsel some participants off-line as to how to air differences of opinion in constructive and polite ways proved fruitless. Finally, a noisome ineffectual office worker at the University of Wisconsin insulted Tom Green, and I was deeply embarrassed for myself, for my forum, and for my university. I immediately started to make a move to remove the offender, but first asked the university attorney if I could do so. If this idiot could insult Tom Green, he would likely sue me too. The attorney replied that if the forum had been advertised as “public,” I should not exclude the offensive member. This changed everything in my mind.

EDPOLYAN was an early demonstration of the fact that people cannot politely discuss important policy issues online in a public forum. This fact has been demonstrated again and again since. I no longer wanted to be associated with EDPOLYAN. I decided to end it. In late 1995, I announced to the subscribers that EDPOLYAN would be taken down in exactly one week, and I told them why. The ensuing discussion was interesting. Many could not believe that I was serious; others suggested ways of controlling the debate so that it didn’t degenerate into trading insults. Some said, “He probably means it; maybe we can create a new list somewhere else.” But I meant what I said. When the week had passed, I sent the command “Del *@* EDPOLYAN” to LISTSERV at ASU.EDU.

But I have got ahead of the story. What about Education Policy Analysis Archives?

LISTSERVs, like EDPOLYAN, had a feature that involved archiving files at the server that could be retrieved by simple command: GET FileXXX from EDPOLYAN @ LISTSERV ASU. A colleague, K. Forbis Jordan, had written article in his area of scholarship, education finance. But Forbis was tenured and too busy helping states address their finance problems to run the journal publication gauntlet. I thought the paper was good and deserved to be read more widely. I asked Forbis if I could archive his paper on EDPOLYAN and announce its availability. He gave permission.

I was not unfamiliar with journal publishing. I edited AERA’s Review of Educational Research from 1968 to 1970, Psychological Bulletin from 1978 to 1980, and American Education Research Journal with Mary Lee Smith & Lorrie Shepard from 1984 to 1986. By 1990, the mystique of journal editing was gone. I knew journal publishing from inside out. And when I archived Forbis’s paper and announced it to the world, I realized that this was just journal publishing. But it was journal publishing with a difference.

A journal could be created and operated as part of my job, and no one would have to subscribe or pay a fee either to publish in the journal or read it. So I created EPAA, Education Policy Analysis Archives, by adding the world “archives” to the old name of the LISTSERV. I asked some of the leading lights of the EDPOLYAN LISTSERV to serve as the Editorial Board. I sent an announcement to EDPOLYAN that a journal dealing with education policy exists and will welcome submissions. I did all this without bothering to ask my department or my university if I could. I asked for no money, because that would inevitably lead to charging readers subscription fees. (In fact, more than one administrator, upon learning of the great reach of this new journal, asked me if there was a way we could make money off of it.) No money to produce; no money to read. If you want to reach a wide audience, make it free. Like Moliere’s bourgeois gentleman who was surprised to learn that he was speaking “prose,” I was surprised to learn eventually that I was publishing in “open access.”

In my humble opinion, I believe that EPAA was instantly successful. The first article published on January 19, 1993, was by a young Australian scholar, Stephen Kemmis: Action Research and Social Movement: A Challenge for Policy Research. On February 2, 1993, I published David Berliner’s 17,000 word article titled “Educational reform in an era of disinformation” as Volume 1 Number 2. Berliner’s contribution gave EPAA instant credibility.

After Berliner’s contribution, submissions were plentiful. A sufficient number of scholars sensed the importance of open access and chose to support it by publishing in EPAA. A larger group, however, remained suspicious. Years later, a PhD student I was advising undertook a study of scientists and scholars reactions to open access publishing. In 1997, William “Skip” Brand interviewed a number of mathematicians, physicists, psychologists, and educationists. The first two categories of scholars reported that they no longer subscribe to paper journals; they no longer depend on peer reviewed research; each morning they checked the archives at Los Alamos to download the most recently archived papers in their field. Psychologists were somewhat more cautious. Although they reported that they had long depended on the “Invisible College” of colleagues who exchange “preprints” of their research to keep up to date, they still subscribed to paper journals. Brand found that the educationists were the most suspicious of open access publishing. They want to know that what they read has been christened as acceptable by their fellow educationists – no open access for them. Tres ironique! An area of study that actually has a paradigm needs no jury of experts to tell them what is worth reading. To this day, I suspect that some educationists continue to believe that papers that are not peer reviewed are infected with some virus of falsehood or incompetence.

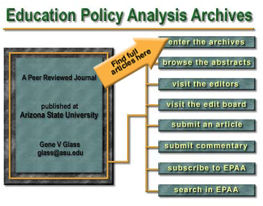

The earliest articles published in EPAA were distributed via email in text only to persons who had joined the mailing list. But EPAA was evolving at the same time the world wide web was evolving. Sometime between 1993 and 1995, EPAA changed from being a text-based email list to being a full-fledged website. I had to learn html coding to turn submitted papers into webpages and Adobe Photoshop to create or incorporate images. It was time consuming but the result was satisfying. By 1996, EPAA looked like this:

EPAA ran like clockwork for many years. Submissions were plentiful. When I received a submitted article, I made an immediate judgment whether it had come to the right place. If not, I sent an email to the authors to try elsewhere. More often than not, the submission was appropriate and I immediately sent the paper to the entire Editorial Board, which in 1993 numbered 26 persons. The message attached to the submitted paper was in effect, “Here’s a submission; if it’s in your area, please review.” Normally, I would receive a half-dozen reviews within a week.

This format of wide distribution of submissions to a large Editorial Board confirmed some of my suspicious that were formed during two decades of editing traditional paper journals. Hardly any submission to EPAA received unanimous recommendations to publish. If unanimity were the standard for a decision to publish, EPAA never would have survived its first decade; in fact it never would have got off the ground. I began to see that articles published in traditional paper journals only made it through the review process by accident of which three reviewers the editor chose. The cynicism that I had developed during the editing of three previous journals was only confirmed by my experiences with EPAA in the 1990s. It is this cynicism that contributes to my understanding of why scientists say, “Send me your preprint; I’ll decide for myself if it makes sense.” It is this cynicism that is the basis of my preference for public debate of education policy issues rather than dissemination of unchallenged, peer-approved opinions.

In late1998, a Mexican scholar, Roberto Rodríguez Gómez of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, wrote me and asked if EPAA would ever consider publishing an article in Spanish. I wrote him back immediately to tell him that I spoke no Spanish and asking him if he wanted to be EPAA’s Associate Editor for Spanish Language articles. He said, “Yes.” The first Spanish language article appeared on August 12, 1999, was Autonomia Universitária no Brasil: Uma Utopia? It was authored by Maria de Lourdes de Albuquerque Fávero. Today, EPAA publishes education policy research proudly in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Monolinguals like myself – well, actually I can handle German and English moderately well – only wish that every article could be published simultaneously in all three languages.

I will break off this account of the history of EPAA at this point, since those of you reading this know its recent history first-hand.

EPAA Spinoffs

By the late 1990s, open access was no longer a novelty. Hundreds of online open access journals publishing academic and scientific research were available to readers at no cost. Perhaps the local interest in EPAA resulted in the creation of a couple more open access online journals and the movement of one long established journal to partial open access form.

Education Review/Reseñas Educativas

Education Policy Analysis Archives had begun publishing book reviews as early as 1995. I appointed a PhD student, Walter Shepherd, the book review editor for EPAA. (Walter was one of several PhD students whom I involved in the work of publishing EPAA. Casey Cobb served as commentary editor for the last two years of his doctoral work. Other students were involved in copy editing and even reviewing submissions.) Although EPAA published a dozen or so reviews of books on education policy in the mid-1990s, it was obvious that books dealing with education policy were just the tip of an iceberg of books dealing with all aspects of schooling. So I decided to create an open access journal of education book reviews. I quickly learned that a librarian at Michigan State University, Kate Corby, had been publishing for some years beginning as early as 1993 via email distribution what she called “brief reviews” of education books. I contacted her and asked if she would like to collaborate in building an open access web-based book review journal. She immediately became one of the many individuals with the foresight to see where academic publishing must go and with enough generosity of spirit to labor without compensation to bring that future about. Education Review, now Education Review/Reseñas Educativas, began on a web server in my office in early 1998. It was time to go back to Photoshop:

Education Review grew rapidly, and I soon discovered that the scope of book publishing in education was huge. I needed help from scholars whose expertise reached farther than statistics and some education policy issues I felt comfortable with. Nick Burbules, a professor of philosophy of education at the University of Illinois, contacted me and expressed his interest in Education Review. So I asked him to serve as a co-editor, which he graciously did starting in 1998 and ending in 2000. The number of individuals willing to devote their talents to the journal was large. By 2002, the following persons were playing important roles in putting out more than 100 reviews a year: Kate Corby (Michigan State Univ.), Gustavo E. Fischman (Cal State LA), Patricia Fey Jarvis (ASU), Nicholas C. Burbules, (Univ. of Illinois), Lynda Stone (Univ. of North Carolina), Lizanne Destefano (Univ. of Illinois), Sherman Dorn, (Univ. of South Florida), Erwin Epstein (Loyola Univ. of Chicago), Gale Sinatra (Univ. of Nevada, Las Vegas), Greg Camilli (Rutgers Univ.), David Blacker, (Univ. of Delaware), Gary Anderson (Cal State LA),

Aimee Howley (Ohio Univ.), Robert Floden (Michigan State Univ.), Thomas A. Callister, Jr. (Whitman College). Kate Corby retired in 2008. She recommended a colleague at the University of Nebraska at Omaha, to be her successor; Melissa Cast-Brede has served as Education Review/Reseñas Educativas since then.

By 2013, ER/RE had published more than 3,000 reviews of education books in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. The editorship passed through a few hands – for example, David Blacker of the University of Delaware served as editor for English from 2012 to 2014 – and for a period the journal was even listed as a project of the National Education Policy Center at the University of Colorado Boulder to bring attention to the new Center. Gustavo Fischman assumed the editorship in 2014.

International Journal of Education and the Arts

Tom Barone, a colleague in the

College of Education, worked in qualitative inquiry and arts education. He was

accustomed to the neglect that these interests suffered at the hands of

hide-bound traditional education researchers. He asked one day if it would be

possible to create an online journal dealing with education and the arts. It

took less than a week in early 1999 to put up the framework of the International Journal of Education and the

Arts. Tom and Liora Bresler of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign served as

Founding Editors, and I got to play with Photoshop again.

Tom and Liora honored me by naming me a co-editor of IJEA even though my credentials in the field of arts education are nonexistent. Fortunately, I was not in any position to make any important decisions. I enjoyed formatting articles that involved pretty or interesting pictures. IJEA has survived by dint of the great efforts of Tom and Liora, who edited it until 2007. It began its 22nd year of continuous publication in 2021 and resides on web servers at Pennsylvania State University.

Journal of American

Indian Education

In 1997, David Berliner was named Dean of the College of Education. He asked me to serve as his Associate Dean for Research. An Advisory Board was formed, and I used my miniscule influence to name a neighbor and good friend to the Board: Jim Furman. Jim was retired from the position of Executive Vice President of the John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. He had for several years administered the MacArthur Genius Awards. He never explained why he had overlooked me for one of his awards, but we did talk about open access. He liked the idea. One day he said, “What would you do with $20,000?” The question posed a dilemma. If I accepted it for EPAA or even ER/RE or IJEA, I would negate my whole argument as to why universities should be publishing open access journals for no cost and at no added expense. The public funds public higher education – and to a considerable extent private universities too through government granted student loans and funds for research and development. Universities are full of individuals whose efforts could be directed more productively toward making the fruits of research available at no cost to the public that has already paid to have it produced. If I accepted Jim’s offer of money, I would have acted as if “outside” or additional money was required to provide the public access to research and scholarship. My university already was paying me handsomely to do something worthwhile. Like most faculty, I had plenty of time that could usefully be dedicated to publishing scholarship free to the public.

But I accepted Jim’s offer anyway. My colleagues at the College of Education had for many years published the Journal of American Indian Education. It was published on paper and mailed to subscribers and had only a few customers – circulation might have been a few hundred. It had been published continuously since 1961. Well, all of those back issues existed only on paper in the stacks of academic libraries. They were important contributions not just for historic reasons but as background for understanding contemporary issues in the schooling of native Americans. I told Jim that I had an idea for how $20,000 could be well spent. We would digitize all JAIE articles from 1961 to the present and make them available via open access. He liked the idea. We had a cocktail party with the staff of the Center for Indian Education. I went back to Photoshop.

Optical character scanning at the time was not quite up to the job of digitizing 40 years of journal articles. But we had $20,000 to pay typists to reconstruct all the articles that then existed only on paper. The job took a year, but the result was a valuable resource for scholars studying American Indian education: http://jaie.asu.edu. Unfortunately, the articles from 1961 to 2000 are not now available at the journal website. Fortunately, they can be accessed via the Internet archive Wayback Machine – Internet Archive:

https://web.archive.org/web/20010203214500/http://jaie.asu.edu/vols.html JAIE is not currently available via open access, but hope never dies.

Current Issues in

Education

Current Issues in Education (http://cie.asu.edu) is an open access peer-reviewed academic education journal produced by doctoral students in the college of education at ASU. It was created in 1998. David Berliner, Jim Middleton, and I served as faculty advisers for several years. Currently it is in its 21st year of continuous publication.

I don’t have an historian’s instincts or training. Undoubtedly there are errors in this account of my forays into academic open access publishing. Surely I have left out the names of dozens of individuals who contributed to this effort in important ways. I would apologize, but they will probably never see this anyway.

~ Gene V Glass

No comments:

Post a Comment